I was watching an interview with Ilya Sutskever (co-founder of OpenAI, former chief scientist, and one of the most important figures in modern AI) when he said something that made me immediately pause the video.

They noted that teenagers learn to drive in about ten hours; meanwhile, AI systems need millions of training examples to do the same thing. Sutskever suggested there’s probably some undiscovered principle behind human learning efficiency, but then added something that caught my attention: “There may be another blocker though, which is that there is a possibility that the human neurons do more compute than we think.”

…Huh. Do they?

Naturally, I had to know if that was true. Well, I’ve since climbed out of that rabbit hole—and what I brought back has left me more than a little worried.

The Scaling Party Is Over

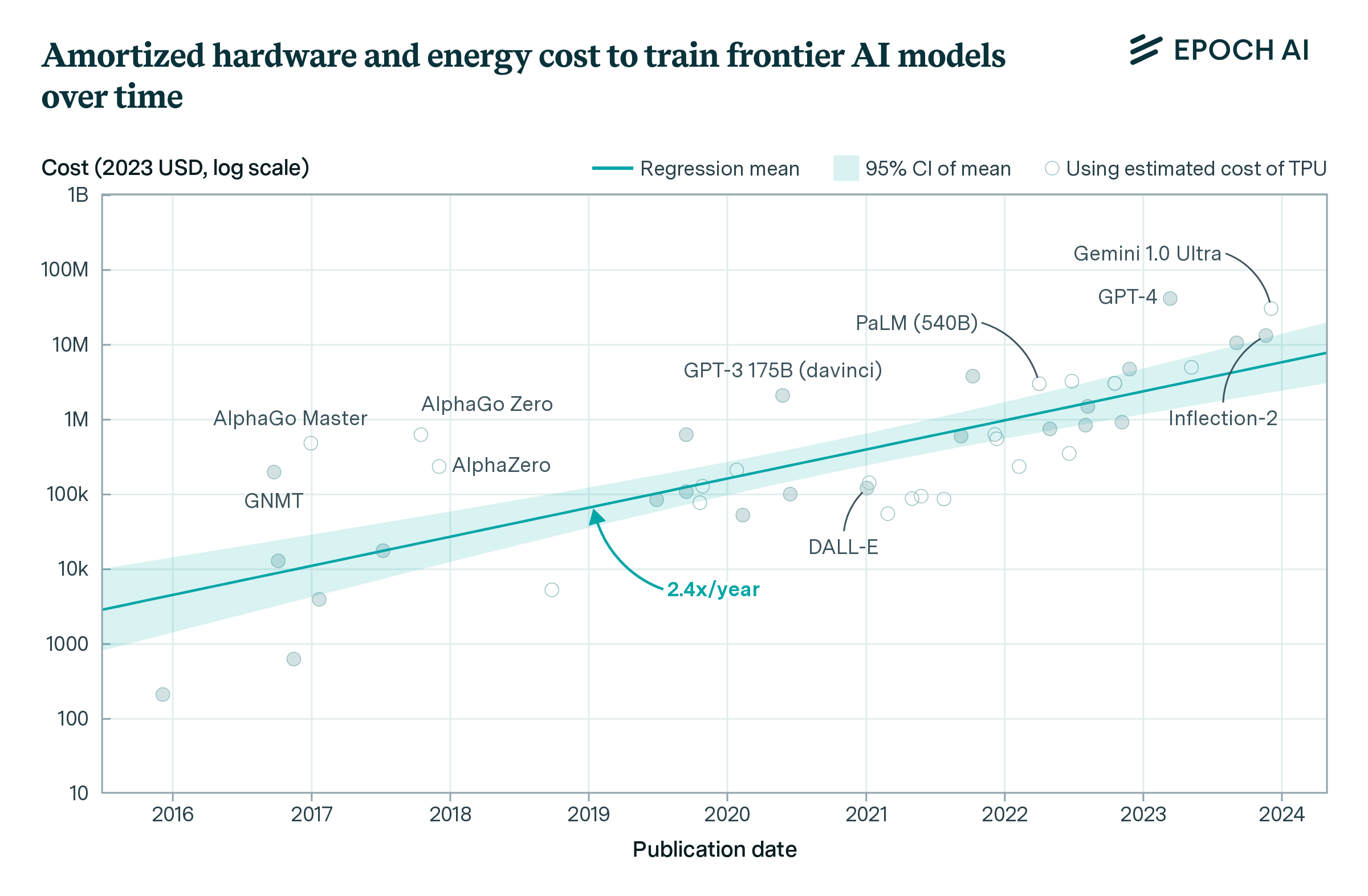

Sutskever didn’t mince words: “The 2010s were the age of scaling. Now we’re back in the age of wonder and discovery once again.” He compared training data to fossil fuel, noting that both are finite resources we’re rapidly exhausting.

The numbers aren’t great. Epoch AI projects we will run out of high-quality text data somewhere between 2026-2032. OpenAI’s long-awaited GPT-5, released this past August, landed with a thud: users called it “underwhelming,” and the backlash was severe enough that Sam Altman admitted OpenAI “totally screwed up” the launch. Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Yann LeCun has been blunt: autoregressive LLMs are a dead end on the path to human-level intelligence.

As Sutskever put it: “Scaling sucked out all the air in the room… everyone started to do the same thing.”

So, why is this such a problem? What are we actually scaling? And are we even scaling the right things?

How These Things Actually Work

Before we go further, it’s worth understanding what’s actually happening under the hood of ChatGPT, Claude, and every other LLM.

Stay with me here—this matters!

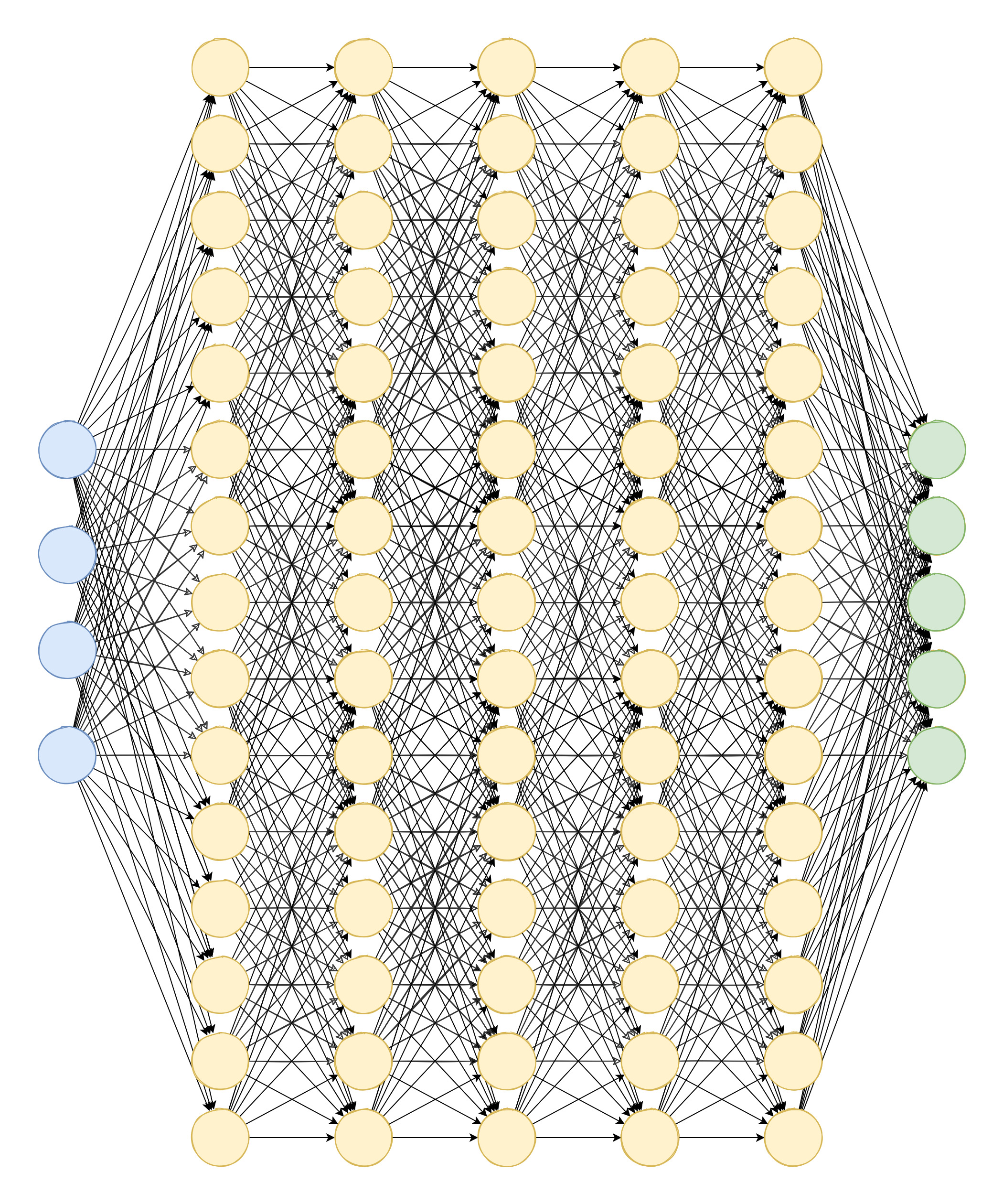

The fundamental building block is something called a perceptron, invented in 1958. It’s a simple concept: take some inputs, multiply each one by a “weight” (basically, how important that input is), add them all up, and if the total exceeds some threshold, output a 1. Otherwise, output a 0.

That’s it. That’s the artificial “neuron.”

Stack thousands of these together in layers, and you get a neural network (basically). The first layer takes in raw data: pixels of an image, words in a sentence, whatever. Each perceptron performs its own multiply-and-sum dance, passes results to the next layer, and so on until you get an output. The “deep” in deep learning just means lots of layers. GPT-4 may have over a trillion of these parameters (the weights and biases that define the model) arranged in around 120 layers—though OpenAI hasn’t confirmed the exact architecture.

The magic (if you can call it that) is in the weights. When you “train” a neural network, you’re really just adjusting billions of these weight values until the network produces correct outputs. Show it a picture of a cat labeled “cat” a million times, and gradually the weights shift until the network can recognize cats it’s never seen before.

How do the weights get adjusted? That’s where a process called “backpropagation” comes in. You run an input through the network, compare the output to what it should be, calculate the error, then work backwards through every layer asking “how much did each weight contribute to this mistake?” Adjust accordingly. Repeat a few billion times.

The thing is, this entire paradigm is based on a model of biological neurons from the 1940s and 50s. Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts proposed that neurons were basically simple logic gates: inputs come in, threshold is reached, neuron fires. The perceptron formalized this. And we’ve been running with that assumption ever since—myself partially included.

Seventy years of AI research built on top of what we thought neurons did. In 1943.

Back to Biology Class (Sort Of)

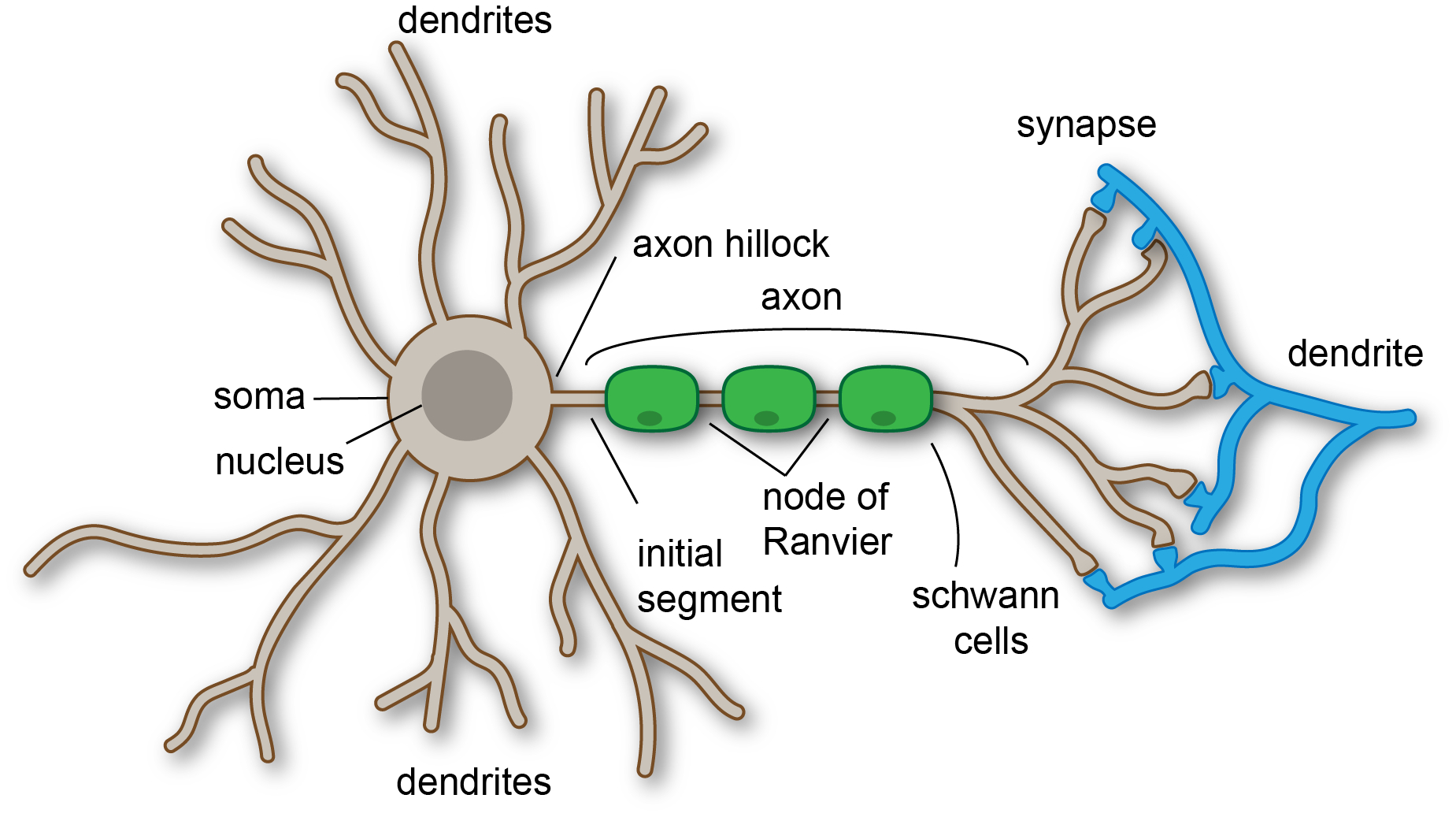

Sutskever’s comment sent me back to what we all (should have) learned in biology class. You know the drill: ions flow across the membrane, a threshold is reached, the neuron fires an action potential. That’s the model. And it’s not unlike how artificial neural networks work. Sum inputs, hit threshold, fire. One event, one output. Simple.

But what if that’s… not actually how neurons work? What if the real computation isn’t happening in the cascade—neurons firing, triggering other neurons, signals rippling across the network—but somewhere else entirely?

Of course, I started digging into the research.

A 2021 study found that a single biological neuron performs computations equivalent to a 5-8 layer artificial neural network. That’s roughly 1,000 artificial neurons to match one real one. Even the researchers were stunned. “I thought it would be simpler and smaller,” admitted David Beniaguev. “I expected three or four layers would be enough.”

The secret lies in the dendrites. For decades, we treated them as passive wires that just collect signals. Turns out they’re more like independent processors. Imagine if every transistor in your computer wasn’t just an on/off switch, but contained its own tiny computer. That’s what we’re dealing with here.

Back in 1969, AI pioneers proved that single-layer networks couldn’t solve the XOR problem (basically, figuring out when exactly one of two inputs is active). This limitation contributed to the first “AI winter” a few years later. The solution? Multi-layer networks.

But biology solved it differently: A 2020 Science paper found that individual compartments within human neurons can solve XOR on their own. Single dendritic branches implement logic that artificial networks need multiple layers to achieve.

“Maybe you have a deep network within a single neuron,” observed computational neuroscientist Panayiota Poirazi. “And that’s much more powerful in terms of learning difficult problems.”

The Training Problem

Every major AI system (GPT-4, Claude, Gemini, LLaMA) trains using backpropagation (that thing I mentioned earlier). It’s an algorithm from the 1980s that calculates how each weight contributed to errors and adjusts accordingly, sending signals backward through the network.

The problem is, brains don’t learn like this!

Backpropagation requires symmetric weights (biological synapses are one-way), instantaneous network-wide error propagation (neurons can’t do this), and labeled training examples (you didn’t learn to walk from a dataset of correct steps). Even Geoffrey Hinton, the guy who helped invent backpropagation, acknowledged in his Forward-Forward Algorithm paper that there’s “no convincing evidence that the cortex explicitly propagates error derivatives.”

And it’s brutally inefficient. Training GPT-4 required an estimated 25,000 GPUs for 90+ days. Your brain? About 20 watts. A dim light bulb. The efficiency gap is estimated at 27 trillion times.

Twenty-seven trillion.

So, we’re hitting data limits, AND our fundamental training approach can’t even scale efficiently.

That’s not a slowdown… That’s a DEAD. END.

I think it’s hilarious how the same CEOs calling for AI to replace human workers never mention that part. If they actually cared about “efficiency,” the math doesn’t exactly work out in AI’s favor right now.

(Some related rabbit holes, if you’re interested: here, here, and especially here.)

There Are Alternatives (But Don’t Get Too Excited)

Luckily, some researchers ARE building systems that exploit biological principles. Dendritic Localized Learning mimics how our neurons actually work: learning happens locally, no backward propagation needed. Dendritic artificial neural networks can achieve similar performance with orders of magnitude fewer parameters.

New hardware is emerging too: Intel’s Hala Point system has 1.15 billion artificial neurons, and IBM’s NorthPole chip achieves 72x better energy efficiency than GPUs in certain scenarios.

But the uncomfortable truth is, no major LLM provider has abandoned conventional training. The entire deep learning ecosystem (PyTorch, TensorFlow, GPU architectures) is optimized for backpropagation. As IBM admitted about NorthPole: “We can’t run GPT-4 on this.”

Replacing backpropagation at scale likely requires 5-10+ years of research, which feels like an eternity in today’s world—especially when trillion-dollar valuations assume continuous exponential improvement.

The Economic House of Cards

Here’s where it gets scary for anyone with a stake in the United States economy. (So, everyone to some extent, right?)

The S&P 500 has effectively become one massive leveraged bet on AI working out. According to Morgan Stanley, the “Magnificent Seven” plus 34 AI ecosystem companies are responsible for roughly 75% of market returns and 80% of earnings growth since October 2022. The other 493 companies in the S&P 500? Up just 25% total.

Nvidia alone—the first company ever to pass a $5 trillion market capitalization—now represents nearly 8% of the entire S&P 500 (and over 12% of NASDAQ). That means at least eight cents of every dollar in your index fund goes to a single chipmaker. Zoom out, and the top five companies compose 30% of the S&P’s total value—double the concentration we saw during the dot-com bubble.

The Shiller P/E ratio, a valuation metric that smooths out short-term fluctuations, recently exceeded 40. It’s only been that high once before in 140+ years of market history: the dot-com bubble. Even 1929, right before the Great Depression, only hit 33. While no single metric can tell the whole story, it’s hard to look at that chart in context and feel calm.

And it’s not just the skeptics ringing alarm bells.

Sam Altman himself admitted he believes an AI bubble is ongoing. Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates co-investment officer, called current investment levels “very similar” to the dot-com bubble. Even the Bank of England has warned of global market correction risks.

The math itself doesn’t look promising, either. AI capital expenditures from S&P 500 tech companies exceeds $400 billion annually. OpenAI only brought in $13 billion in 2025 revenue while potentially losing $12 billion in a single quarter.

And the returns? Earlier this year, an MIT study found that 95% of AI pilot projects failed to deliver any discernible financial savings or uplift in profits.

Billions in, nothing out.

One analyst called it “the biggest and most dangerous bubble the world has ever seen.” That might be hyperbole—nobody can predict the future, and I’m not trying to be alarmist here, but the sheer number of irrational factors at play is impossible to ignore. AI investment now accounts for nearly half of US GDP growth. Major institutions are making bets that seem completely ungrounded in financial reality. If even a fraction of this unwinds, we’re not just looking at a tech correction. We’re looking at a recession—or perhaps something worse.

Yes, of course I could be wrong. But a lot of very wealthy people seem to be acting like the music will never stop, and that bothers me deeply (for numerous reasons).

Oh, Don’t Worry: You’re Already Paying for This

Even if you’ve never touched ChatGPT, you’re subsidizing AI’s infrastructure build-out through your electricity bill.

A Bloomberg analysis found wholesale electricity now costs up to 267% more than five years ago in areas near data centers. In the PJM grid (that’s 65 million people across 13 states), consumers will pay $16.6 billion for power supplies to meet data center demand through 2027. About 90% of that is for data centers that haven’t even been built yet.

Residential electricity prices rose 6.5% nationally between May 2024 and May 2025. Some states got hit harder: Maine up 36%, Connecticut up 18%, with Washington State not far behind at 12.6%. A Carnegie Mellon study estimates data centers could increase average US electricity bills by 8% by 2030, potentially exceeding 25% in high-demand areas.

“Households are partially subsidizing the AI data center expansion,” as one UPenn researcher put it.

And it doesn’t stop at electricity. The AI buildout has strained the entire semiconductor supply chain—GPUs, memory, storage, all of it.

AI data centers have redirected global DRAM production toward specialized chips, creating shortages of regular RAM for the rest of us commoners. Prices are up roughly 50% this year, with another 30-50% expected. Major brands like ADATA and Corsair have been rationing orders because they can’t source enough chips. Beloved memory brand Crucial has actually exited the consumer market; Micron decided AI chips are more profitable than selling RAM to the rest of us. (Side note, that last one hurts… a LOT. Goodbye, Crucial—y’all made awesome components.)

New fabs take 3+ years to build, so even if manufacturers broke ground today, relief wouldn’t arrive until late 2028. Silicon Motion, one of the world’s largest SSD controller manufacturers, has a front-row seat to the crisis. Their CEO put it bluntly: “We’re facing [what has] never happened before: HDD, DRAM, HBM, NAND… [will all be] in severe shortage in 2026.”

So What Does This Mean?

Let’s take stock. The technology itself is hitting fundamental limits—built on a flawed model of how neurons actually work, trained with methods that can’t scale efficiently, running out of data to learn from. The alternatives are a decade away. Meanwhile, we have trillion-dollar valuations, 95% of AI projects showing zero returns, component shortages across the board, rising consumer costs, and even the people building this stuff admitting it might be a bubble.

I keep coming back to that Sutskever quote: “There may be another blocker though, which is that there is a possibility that the human neurons do more compute than we think.”

It’s not a possibility, though… it’s confirmed. Single neurons match the computational depth of multi-layer networks. Dendrites solve problems that stumped early AI. The brain achieves remarkable computation on 20 watts through principles we’re only beginning to understand.

The current LLM paradigm (scaling transformers with backpropagation on internet data) has delivered remarkable progress. But the data is running out, the compute costs are unsustainable, the architecture may be fundamentally limited, and we’ve bet an uncomfortably HUGE portion of the entire American economy on it continuing to work.

The next leap in AI won’t come from more GPUs. It’ll come from finally understanding what our own neurons have been doing all along.

Will we change course before the bill comes due?

I wouldn’t bet on it. But then again, past performance is not indicative of future results.

Want more? I’d recommend watching Sutskever’s full interview and/or a long walk.