VPN companies have spent millions convincing you that hiding your IP address is the key to online privacy. Flip the switch, and you disappear. Your ISP can’t see you. Websites can’t track you. You’re anonymous.

There’s just one problem: your IP address was never the most interesting thing about you.

In fact, I built something to prove it. The experiment below uses a series of tests to perform something called browser fingerprinting, and it’s why your VPN isn’t making you private.

Did you try it? None of those checks were unusual: screen size, timezone, fonts… and yet, odds are, you’re now completely unique, possibly the only person on Earth with that exact configuration. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) discovered this over a decade ago, and the technology has only become more effective since.

What’s Being Collected

Back in 2010, the EFF ran a groundbreaking experiment called Panopticlick. They collected browser characteristics from nearly half a million visitors and found that 83.6% were uniquely identifiable—not by IP address, but by the combination of mundane technical details their browsers freely shared.

With Flash or Java enabled? That number jumped to 94.2%.

The technique has gotten more sophisticated since then. Today, modern fingerprinting collects:

- Screen properties: Resolution, color depth, pixel ratio

- Hardware signatures: CPU cores, available memory, graphics card model

- Software configuration: Installed fonts, browser plugins, language settings

- Rendering quirks: How your specific hardware draws invisible test images (canvas fingerprinting), processes silent audio (AudioContext fingerprinting), or handles WebGL operations

A 2018 study analyzed over 2 million fingerprints collected from a major French news site. The researchers found 33.6% of fingerprints were unique—far lower than the 83.6% the EFF found in 2010. That sounds like an improvement. However, there’s a catch: that study used the same limited set of attributes from years earlier. Commercial fingerprinting has gotten better since then. Significantly better. Fingerprint.com, which serves over 6,000 customer websites as of 2023, claims 99.5% identification accuracy with their commercial product.

And this is all without adding behavioral biometrics like typing rhythm and mouse movement patterns, which some banks already use to verify your identity.

The Math: How This Narrows You Down

Stay with me here, this matters!™

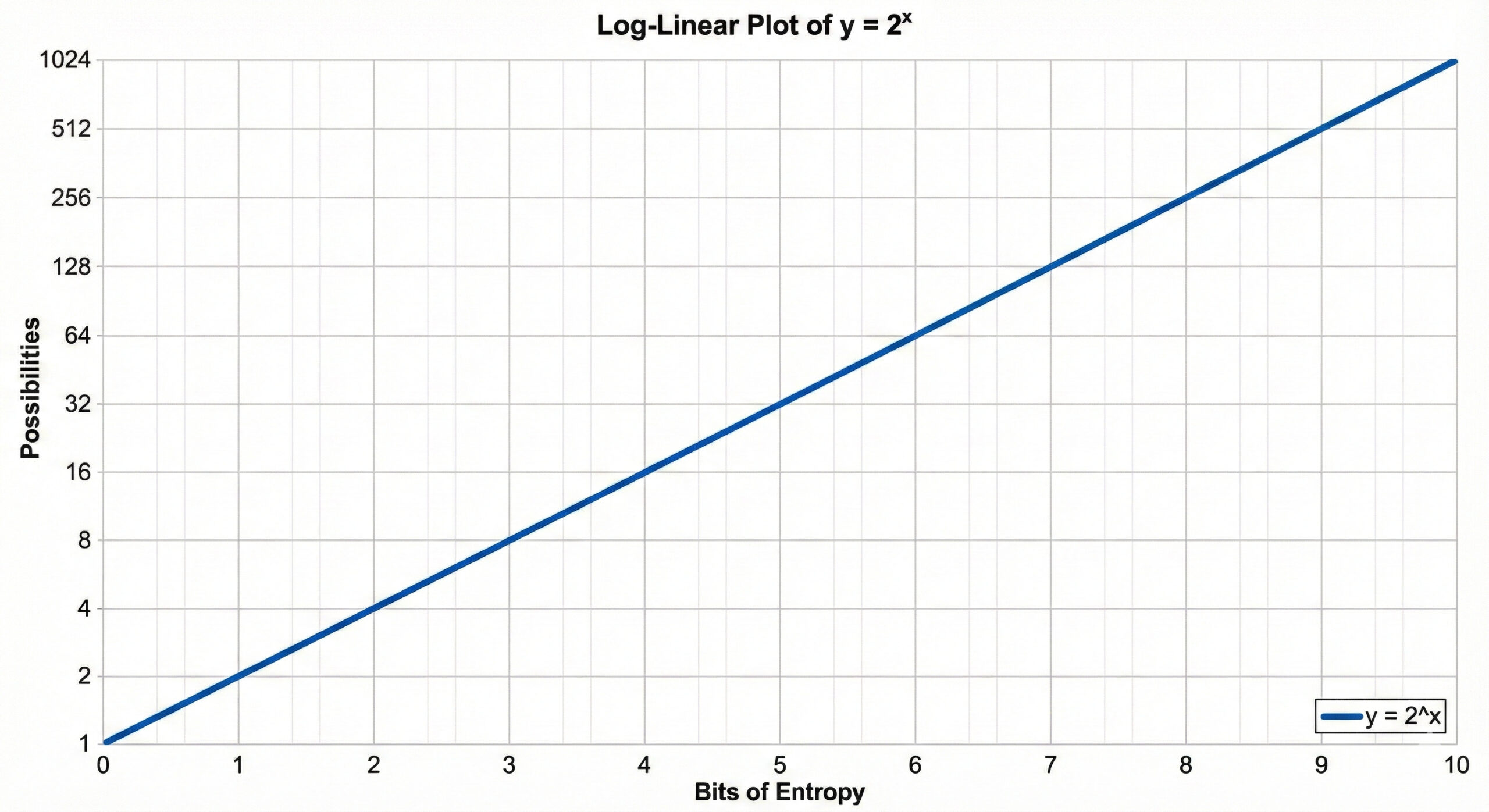

Each attribute contributes what researchers call “entropy,” measured in bits. If you’ve ever wondered why computers love the number 2, it’s because at the lowest level, everything is binary (ones and zeros, on or off, yes or no). A “bit” is one of those binary choices. That’s why we use powers of 2 when calculating entropy.

In other words, 1 bit of entropy cuts the crowd in half (two possibilities).

Two bits narrows it to a quarter (four possibilities).

Ten bits gets you to 1-in-1,024.

Twenty bits? 1-in-a-million.

The formula: 2(entropy bits) = the size of the crowd you’re hiding in.

If an attribute has 10 bits of entropy, that’s 210 = 1,024. You’re one of 1,024 people who share that value.

Flipping back to browser fingerprinting, here’s what Eckersley’s research found for common attributes:

| Attribute | Entropy | Narrows You To |

|---|---|---|

| Browser plugins | 15.4 bits | 1 in ~43,000 |

| Installed fonts | 13.9 bits | 1 in ~15,000 |

| User-Agent (browser/OS) | 10.0 bits | 1 in 1,024 |

| Screen resolution | 4.8 bits | 1 in ~28 |

| Timezone | 3.0 bits | 1 in 8 |

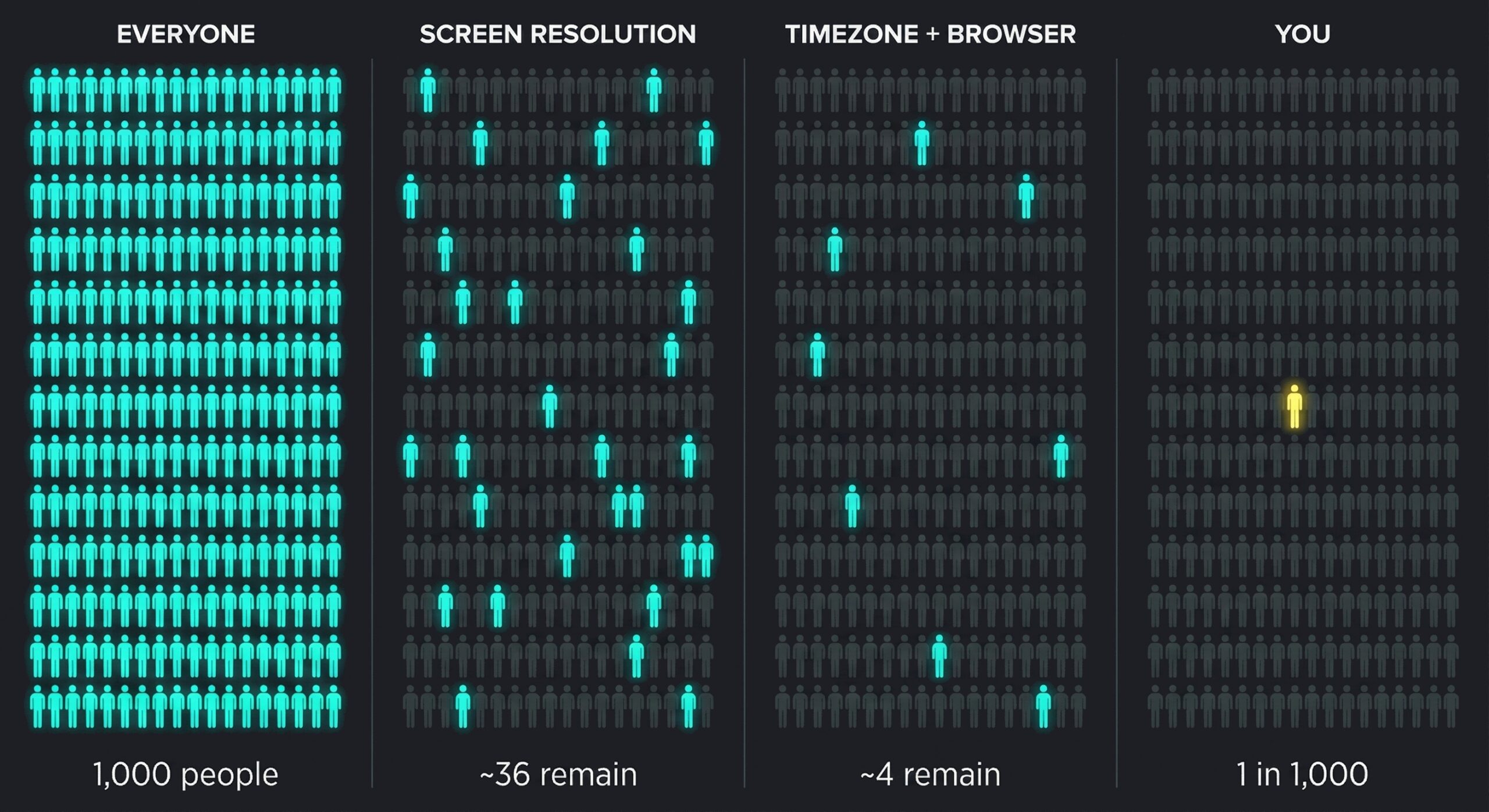

The thing is, this entropy stacks. When you combine attributes, you add the bits together (which is the same as multiplying the crowd sizes). Screen resolution (4.8 bits) plus timezone (3 bits) = 7.8 bits total, or 2^7.8 ≈ 223. You’ve gone from “1 in 28” to “1 in 223” by knowing two things about you.

Keep adding attributes, and by the time you’ve combined a dozen, you’re often the only person on Earth with that exact combination.

The Panopticlick study found that the average browser carried at least 18.1 bits of identifying information. The EFF calculated that this made browsers unique among 286,777 others—that’s why 83.6% of browsers in their study were completely unique.

And none of that includes your IP address.

That 1-in-286,000 uniqueness is calculated without looking at where you’re connecting from. Your IP is the cherry on top of an already-unique fingerprint. In other words, when a VPN hides your IP address, it’s hiding the one identifier that was almost redundant to begin with.

What VPNs Change

When you connect to a VPN, the following characteristics change:

- Your IP address

- Your approximate location on Earth (based on that IP)

…

That’s it. That’s the list.

What VPNs Don’t Change

- Your screen resolution

- Your timezone

- Your browser and version

- Your operating system and version

- Your installed fonts

- Your browser plugins and extensions

- Your CPU core count

- Your graphics card model

- Your graphics card’s canvas rendering signature

- Your language settings

- Your “Do Not Track” setting (ironic, right?)

- Your touchscreen capabilities

- Your battery status (on some browsers)

- How you type

- How you move your mouse

- How you scroll

…and dozens more attributes that make up your fingerprint.

RTINGS.com tested this directly. They collected fingerprints from a single PC while connected through four different VPNs and once without—the fingerprint hash was identical in every case. In a separate test, they fingerprinted 83 office laptops with nearly identical specs: every single one was unique.

This isn’t a flaw in any particular VPN service. Rather, it’s a fundamental limitation of what VPNs do. They encrypt your connection and mask your location. They don’t, and can’t, change your device’s identity.

The VPN industry knows this. A 2021 Consumer Reports investigation found that 75% of major VPNs either inaccurately represented their products or made “hyperbolic or overly broad claims” about protection. In July 2022, citing this research, Representative Anna Eshoo and Senator Ron Wyden urged the FTC to address the industry’s “abusive and deceptive data practices.”

And those “no-logs” policies? PureVPN provided the FBI with user data in a 2017 cyberstalking case despite advertising “zero logs.” IPVanish did the same for Homeland Security. In 2020, seven Hong Kong-based VPNs, including UFO VPN, Super VPN, and Flash VPN, were found to have left 1.2 terabytes of user logs on an unsecured public database, including clear-text passwords and browsing history. All seven had claimed “no-logs” policies.

Why This Matters (The “Nothing to Hide” Conversation)

This is usually where someone says, “I have nothing to hide, so why should I care?”

Look, I get it. And I’m not here to lecture you. But let me start with something that hits your wallet right now.

You’re Already Paying More

In January 2025, the FTC released findings from their investigation into what they call “surveillance pricing.” Companies are using your personal data (location, browsing history, purchase patterns, even your mouse movements) to charge you individualized prices for the same products.

Here’s a hypothetical example from their report: a company knows you’re a new parent (from your recent baby product purchases) and that your baby is sick (from your recent searches). They show you higher-priced baby thermometers at the top of your search results. Because desperate parents will pay more.

In 2012, The Wall Street Journal revealed that Orbitz was steering Mac users toward pricier hotels, knowing they’d be more likely to book them. CBS News and other outlets confirmed the practice at the time.

The Markup found people paying ~400 times more per megabit than their neighbors for internet service based on location data.

A 2015 study found that The Princeton Review charged different prices for the same online SAT tutoring depending on ZIP code, with prices ranging from $2,760 to $3,240 for an identical 24-hour package.

When the FTC first announced the investigation in July 2024, Chair Lina Khan warned: “Firms that harvest Americans’ personal data can put people’s privacy at risk. Now firms could be exploiting this vast trove of personal information to charge people higher prices.”

This “nothing to hide” viewpoint is costing us money. Right now. Today.

The Deeper Problem

But let’s go beyond your wallet.

Journalist Glenn Greenwald has a response to the “nothing to hide” argument. In his TED talk on privacy, he points out that this worldview assumes there are two kinds of people: good people and bad people. Bad people have reasons to hide things. Good people don’t.

But as Greenwald notes, people who say they have nothing to hide are really saying they’ve agreed to make themselves so harmless, so unthreatening, so uninteresting that they don’t fear surveillance. He offers a challenge: email him your passwords so he can publish anything interesting he finds. After all, if you have nothing to hide, what’s the problem?

“Not a single person has taken me up on that offer,” he notes.

We all have things we don’t share publicly. Not because they’re illegal, but because they’re private. Conversations with a therapist. An embarrassing medical search. A political opinion we’re not ready to defend at Thanksgiving dinner. A joke that would sound terrible without context.

“Nothing to hide” assumes you know what you’ll need to hide, that the rules never change, and that everyone with access to your data will always be benevolent.

History hasn’t been kind to those assumptions.

When Data Gets Weaponized

Think about how reality TV works. Contestants routinely get the “villain edit,” where producers splice together out-of-context moments to construct a narrative. Hours of footage compressed into a character arc decided before filming even began.

Now imagine that, but with decades of your digital footprint. Every search query, website visited, message sent, location tracked.

A sufficiently motivated adversary could cherry-pick that data to paint almost anyone in a damning light. And unlike reality TV contestants, you don’t get a reunion episode to set the record straight.

In 2004, the FBI wrongly arrested Brandon Mayfield for the Madrid train bombings based on a fingerprint match that wasn’t a match. In 2020, Robert Williams became the first known American wrongly arrested due to facial recognition. Police showed up at his home and handcuffed him on his front lawn, in front of his wife and two young daughters, based on an algorithm’s mistake.

And those are cases where physical evidence was at least involved. The Death Penalty Information Center documents numerous cases where people were likely executed based on fabricated or faulty evidence, including Cameron Todd Willingham in Texas, put to death in 2004 for a fire that forensic experts later determined wasn’t even arson.

Data doesn’t expire. Digital fingerprints don’t fade.

Edward Snowden put it simply: “Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.”

The Bigger Picture

…Because what piece about surveillance would be complete without mentioning 1984, right? The fact that this reference is a cliché is actually the point: we’ve been warning ourselves about this for 76 years and built the damn infrastructure anyway…

George Orwell’s 1984 wasn’t about catching specific crimes. It was about creating a society where people self-censored because they might be watched at any moment. As Greenwald put it: when we know we could be monitored, our behavior becomes “vastly more conformist and compliant.”

We’re building that infrastructure now, with better marketing.

What about vulnerable populations? A 2023 Bark study analyzing their monitored accounts found that 8% of tweens and 10% of teens encountered predatory behavior online. Internet safety organization Enough Is Enough cites similar statistics on online predator contact rates. Those predators use the same data trails everyone else does. Knowing where a child lives, what school they attend, what their interests are, when their parents aren’t home: all of it is traceable through the same mechanisms that let advertisers serve you targeted ads.

Privacy isn’t about hiding secrets. It’s about protecting people.

What Actually Helps (Hint: It’s Not Just Your VPN)

I’m not saying VPNs are useless. They’re genuinely good at what they’re supposed to do:

- Preventing your ISP from logging your browsing history

- Skirting your provider’s bandwidth caps or traffic restrictions

- Accessing geo-restricted content

- Protecting traffic on untrusted networks

- Adding a layer between you and direct IP-based tracking

- Securely connecting to work or home networks

- Hosting services when your ISP’s router restricts port configuration (my primary use case!)

Here’s what that first point looks like in practice:

| Item/Activity | Without VPN | With VPN |

|---|---|---|

| Your real IP | ✓ Visible | ✗ Hidden |

| DNS queries (sites you look up) | ✓ Visible | ✗ Hidden |

| IP addresses you connect to | ✓ Visible | ✗ Hidden (just the VPN server) |

| Timestamps | ✓ Visible | ✓ Visible |

| Data volume | ✓ Visible | ✓ Visible |

| Page content (HTTPS) | ✗ Encrypted | ✗ Encrypted |

| Page content (HTTP) | ✓ Visible | ✗ Hidden |

But if you believe that flipping on a VPN makes you completely anonymous online, you’re operating under a false sense of security that VPN marketing has carefully cultivated.

As the Web Almanac 2024 documents, fingerprinting has become an attractive alternative for trackers as browsers crack down on cookies. Defending against it is limited, imperfect, and comes with an uncomfortable irony.

The catch? Using privacy tools can make you more identifiable, not less.

If only a small percentage of users have a particular setting enabled, that setting becomes a signal. You’re no longer hiding in a group. You’re the one person wearing a neon sign that says “I’M TRYING TO HIDE.”

Researchers put it bluntly in the original Panopticlick study: “Paradoxically, anti-fingerprinting privacy technologies can be self-defeating if they are not used by a sufficient number of people.”

Browser-Level Defenses

Tor Browser makes all users look identical. It’s effective but slow, and many sites block Tor users entirely.

Firefox’s Enhanced Tracking Protection includes fingerprinting defenses that spoof common attributes and block some fingerprinting techniques. It breaks some websites but significantly reduces uniqueness. The problem? As of 2022, only about 0.48% of Firefox traffic had the most aggressive protections enabled, which means the very act of enabling them identifies you as one of the tiny minority who did.

Brave’s fingerprint randomization adds noise to canvas and WebGL outputs. Recent research suggests sophisticated analysis can partially defeat this, but it’s better than nothing, and Brave has arguably enough market share that you’re not immediately flagged as unusual.

Browser extensions present the same paradox. They can block trackers, but they also make you more fingerprintable. The safest approach uses only extremely high-adoption extensions like uBlock Origin that millions of others also have.

Personally, uBlock Origin is the only browser extension I install on every device. It’s been around forever, it’s open source, it’s effective, and it has enough users that you won’t stand out for having it.

The uncomfortable truth is that fingerprinting-resistant browsing requires trade-offs most people won’t accept. Websites break. Performance suffers. Convenience disappears.

The Alternative: Poison the Well

(The data kind. Not the people kind.)

Here’s where my thinking has shifted.

The traditional approach is defensive: block trackers, hide your identity, leave no trace. But hiding makes you stand out. Trying to disappear is itself a signal.

So instead of leaving one set of footprints in the snow and doing a bad job of covering them up (which both fails to hide your tracks and shows you’re trying to hide), what if you left footprints going in every direction?

This is the data poisoning approach. You don’t become invisible; you become unintelligible. You drown your signal in noise.

Think of it like military chaff: those clouds of metallic strips that aircraft deploy to confuse radar. Your real signature is still in there somewhere, but good luck finding it among a thousand false returns.

Tools for Data Poisoning

Tools like AdNauseam (built atop uBlock Origin) take this approach: they block ads from displaying and silently click on them in the background, polluting your ad profile with random interests. Some tools can run garbage searches to muddy your search history. The goal isn’t to prevent data collection; as far as I’m concerned, that ship has sailed. Instead, the goal is to make the collected data useless.

Again, though, we face a problem: if these tools become detectable, ad networks can simply discard the noise. Use of these tools could become an identifiable attribute all by itself (that paradox again). But there’s something to be said for making surveillance expensive rather than impossible. Every false signal they have to filter out is computational cost. Every garbage profile is wasted ad spend.

The rules shifted while we were still playing defense. Time to change the philosophy.

You’re not going to win a war of perfect privacy against trillion-dollar surveillance infrastructure. But you can make yourself a bad investment. You can be more trouble than you’re worth.

Not a perfect strategy—but better than the alternative.

The Bottom Line on VPNs

Your VPN is a tool, not a cloak of invisibility. It does specific things well; anonymity isn’t exactly one of them.

Using a VPN to watch British Netflix from America? Carry on. Keeping your ISP out of your business? Fair enough.

But if you think a VPN makes you untraceable, your browser is announcing your identity to anyone who asks.

The first step to real privacy is understanding what you’re protecting against, and what your tools do.

As for changing your browser’s fingerprint? The specifics vary wildly by browser, OS, and threat model—and most tweaks either break websites or make you more identifiable (that paradox again). For those who want to try anyway, Privacy Guides is a great resource, as is the EFF’s Surveillance Self-Defense guide.

The next time you see an ad for a VPN, remember: Your IP address is never the most interesting thing about you.

NOTE: The application I built for this post, FOUNDprint, is not nearly as robust or as powerful as other fingerprinting tools. For more on your unique fingerprint, check out the EFF’s Cover Your Tracks or AmIUnique.